Senators have been having a tough time the last few weeks and the institution is looking a lot less like an institution of sober second thought and more like a frat house. But, even if Harper is now regretting his choices and even though he may want senate reform, the recent events do nothing to help motivate change.

Changing the Senate is fraught with risk as any potential change threatens the balance of political power in this country.

The arguments for reform certainly have some merit on their face. Consider the following reasons: (1) it is a waste of money given the work that is done by Senators; (2) Senators are not accountable to anyone, even the person who appointed them; (3) the institution does not fulfill its mandate to represent the provinces; and, (4) the Senate does not sufficiently exercise independent oversight of House activity. This laundry list is of my own, but it captures much of the debate.

Faced with arguments such as this and the probable situation that Canadians do not fully see the benefits to a Senate, we would not expect much support within the public for the status quo.

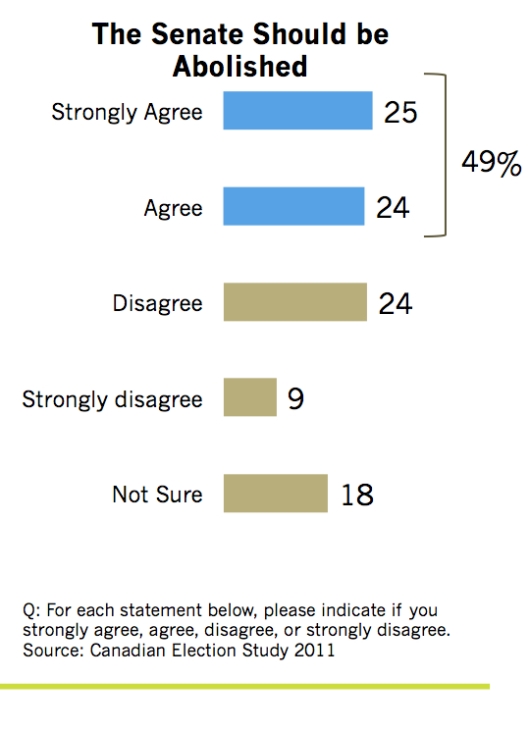

A simple question about its future, in this case abolition or not, does elicit a preference for change. Almost half of Canadians (49%) agree that the Senate should be abolished against only 33% who disagree. Taken from the 2011 Canadian Election Study, this provides directional support for change but it is not overwhelming support. And, of course, abolition is the easiest choice because it does not open up the debate about how to reform or change the institution.

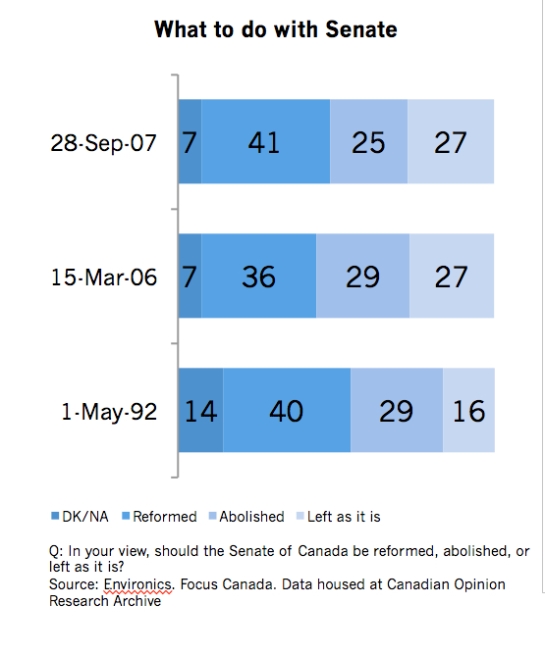

Of course, debate over the future of the Senate is not just being framed in terms of the current Senate or no Senate. Reform is another option and when Environics included this option in polling over the past twenty years it found a plurality is in favour or reform rather than abolition. In fact, 27% would prefer to leave it as it is in the last wave of the study. Interestingly, there has been virtually no movement in public opinion since 1992.

The issue becomes even more complicated when we start probing the nature of the reform that Canadians would support. Our strong commitment to democracy means that 86% would prefer that a reformed Senate be elected directly by the people (Environics, Focus Canada, 2007). No doubt it is this underlying democratic commitment that is generating some of the current appetite for reform. We did not choose these people and they are not representing us.

The issue becomes even more complicated when we start probing the nature of the reform that Canadians would support. Our strong commitment to democracy means that 86% would prefer that a reformed Senate be elected directly by the people (Environics, Focus Canada, 2007). No doubt it is this underlying democratic commitment that is generating some of the current appetite for reform. We did not choose these people and they are not representing us.

There is, however, no consensus on the composition of the Senate and this is, perhaps the most difficult reform to address. Originally, the Senate was meant to be a place of regional representation (thus representation by population was eschewed for provincial/ regional representation). In the same Environics surveys, when asked to choose between having the an equal number of senators from each province or having the number for each province based on the size of the population, Canadians are slightly more likely to prefer population based allocation, but 41% would prefer equal number per province.

Reform, other than the easy step of letting the people decide, is then fraught with political division within the public.

The challenge in reforming the Senate, is that public opinion offers, at this time, so little in terms of helping to navigate the critical details about how an elected Senate would function and be composed. These details are likely to involve an elite-led process unless the Supreme Court rules that some aspects (e.g. the change from appointed to elected) of Senate Reform is wholly within the Federal jurisdiction. Baring this, the requirement for sufficient elite consensus across the country seems lacking.

The public can get annoyed with the current system and tell pollsters they prefer an elected process for the Senate but they are only one player and their annoyance is unlikely to turn into sufficient priority (as compared with more pressing needs such as the economy or health care) to motivate the political class.

More importantly, as yet, the public is insufficiently engaged to truly tell us how they envision the future of the institution. Such as vision, must reflect a true understanding of the consequences for how democracy and government will work in Canada. Such a vision is the only real way Canadians could drive the process for reform.

Public opinion will no doubt matter in the playing out of the politics of institutional reform but one expects it is more likely to act to quash options (and maybe even compromise) rather than directing how political leaders try to sort reform out.

For those interested in reform, some form of deeper citizen involvement and engagement will be necessary. A citizen assembly seems most promising but even here the issues of substantive Senate reform — beyond abolishment — raise potentially intractable issues of political power.

What do you think? Do you want or hope for Senate reform?