Yesterday, the Conference Board of Canada issued a news release indicating that confidence in Canada “took a dive in April”. This counters somewhat the findings from the most recent TNS poll which shows confidence at its highest level since April 2008. Survey timing, question items, and index construction, no doubt explain the difference but what does confidence tell us?

Consumer confidence is generally presented as an important metric in understanding the economy. Poor, or low, confidence means economic trouble and good, or high, confidence means economic growth/stability. In 2008, I wrote about the role of consumer confidence as a barometer of consumer spending and had this to say about the link:

Consumer spending is the engine in a modern economy and, while we expect spending to decline when one’s personal situation is negative (ie. when one has lost his/her job), spending can also erode out of fear of losing one’s job (Jenkins)

Consider, for example, the current economic downturn which impacted Canada in 2008. For most of the previous four years,Canada consumer confidence expectations for the future (according to the TNS Canadian Facts polling) were stable even as evaluations of the present continued to rise. In fact, in November of 2007 the Present Situation Index reached its highest level, just months before confidence would start to decline. While expectations did not lead the downfall in confidence, they have led (for the most part) the improvement.

expectations for the future (according to the TNS Canadian Facts polling) were stable even as evaluations of the present continued to rise. In fact, in November of 2007 the Present Situation Index reached its highest level, just months before confidence would start to decline. While expectations did not lead the downfall in confidence, they have led (for the most part) the improvement.

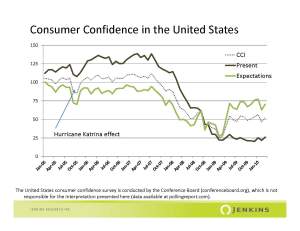

In the United States, there is a similar pattern in that expectations did not lead a decline in the present evaluations. It is interesting, however, that while Americans have increased their optimism about the future, they still think things are quite poor relative to their assessments several years ago.

It appears that confidence is often shaken by exogenous shocks to the system that disrupt the link between one’s actual economic context (job status, savings, expenses) and one’s perceptions of the strength of the economy. If the shock is brief enough (e.g. when Katrina hit causing a major, short-term spike in fuel costs), things return to normal fairly quickly.

When the shock is bigger, the effect is more lasting. The recession is really a shock because the bad news spreads quickly so that even people who have job security become aware of the economic downturn. And, of course, these people did not see it coming. Nevertheless, even in these situations when perceptions turn gloomy, fairly quickly, one sees that people start to expect improvement. In Canada these expectations appear to be borne out but in the United States, the public remains rooted in deep pessimism about the economy.

Confidence is an elusive concept, especially when applied to a future state. But, of course, it is the future state that confidence is most relevant because consumer spending occurs now, presumably, because people are confident that things will get better (or not get worse). For this reason, consumer confidence results continue to give us an important reading on how people are thinking about their finances.

The short answer is that while Canadians are moving toward a more confident posture, Americans remain deeply concerned… despite their optimism for some better future. That said, consumers don’t seem to give us very good warning signs of trouble coming.