A couple of years into the decade and it seems possible that the decade will be defined in terms of its impact on the size and nature of public services/ benefits? Backlash against austerity are already occurring in Greece and there is considerable uncertainty about the willingness of politicians and publics to accept a “right-sizing” of public services.

Ontario is not Greece and Canada is not Europe but the Drummond report (released today) certainly takes the notion of “right-sizing” as a key starting point. But getting the budget in Ontario into balance will not be easy.

To balance the budget, the province must target a spending level in 2017–18 that is 17 per cent lower than the sum found in the Status Quo Scenario — a wrenching reduction from the path that spending is now on (Exec Summary).

The Commission’s recommendations are detailed and potentially transformative but they won’t be easy. This is particularly true given that reducing public services benefits will no doubt constrain economic growth and contributing to a further erosion on the revenue side. Eventually, reducing the deficit has a huge upside by reducing the cost of servicing the debt but getting there will be painful for some.

A look back at the 90s

In Canada, we have an interesting past experience to draw upon. After the Conservative government was unable to significantly reduce spending in the late 80s, Canada had incredible success at reducing the deficit in the 1990s.

Between 1995 and 2007, we moved from a serious deficit situation to a net surplus position before falling back into deficit for 2008. Consequently, there was a steady and dramatic decline in the share of debt to GDP from 57 per cent to under 30 per cent.

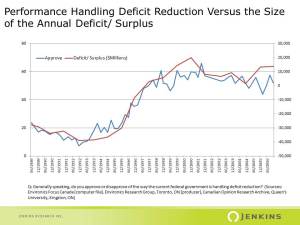

What is interesting is that the success was reflecting in public opinion. Across the period, Environics asked about public approval of “the way the current federal government is handling deficit reduction?”. When we map approval against the size of the surplus, one can see that there was broad recognition that the government was doing a better job.

The recognition came, in part because, Canadians became convinced that the issue was a “crisis”. Between 1989 and 1992, Decima found a rise in public view that the deficit was getting worse from 48.5% to 71.1%. A view that the governing Liberals certainly helped disseminate once they had a majority and were able to take action on the deficit.

I think many Canadians look back and view the deficit reduction as a national accomplishment which raises the question, how will they approach the next wave?

Looking forward

We can view the Drummond report as a transparent attempt to ratchet up the sense of crisis in Ontario. The Prime Minister has been doing the same thing to justify changes at the federal level. Crisis helps sell change because in part its appears non-ideological.

Getting the deficit on the agenda is, of course, difficult because the deficit and debt is a shared liability whereas government spending has clear interests. The groundwork is clearly being laid but where public support will go is unclear, especially when:

- we have already been through this at the national level (this might make it easier for some to accept but it could also generate frustration that we got back into the mess).

- in Ontario, the Liberal government which is now being tasked with the leadership on this issue is the one that has ratcheted up spending. This is a unique situation.

- Canadians are not particularly optimistic about the economy.

- In general, we tend to view government inefficiency/ waste as a major cause of deficits which makes real cuts harder to make and sell.

If the Liberal government can maintain support of the House they have a chance to be bold in the next two years and create a different environment leading into the next regularly scheduled election.

What do you think their chances are?