Public opinion change is not unheard of but when it comes to fundamental beliefs and values, we expect change to take place slowly, if at all. The evolution of Canadian beliefs about same-sex marriage provide an interesting example of dramatic changes that both presupposed and reacted to court decisions.

Courts played a key role in Canada but public opinion was not an idle bystander.

This is telling as Americans look to an upcoming Supreme Court decision about same-sex marriage that will no doubt shape the political discourse there.

Court decisions were certainly critical points in the evolution of public opinion on the issue. For timelines of the issue see the CBC website. Notably, courts ruled in the early 90s that discrimination based on sexual orientation was protected, that same-sex couples have the same benefits and obligations as opposite-sex common law couples (Supreme Court, 1999), and in 2002 the Ontario Superior Court rules that prohibiting same-sex marriage is unconstitutional. Ruling on same-sex marriage in other provinces followed until eventually the Parliament of Canada passed a law defining marriage to include same-sex relationships in 2005.

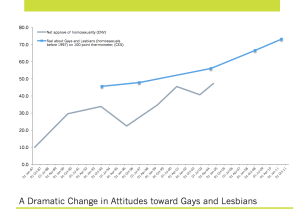

Throughout the period of the 1990s Court decisions were in line with and reflected a growing tolerance toward homosexuality.  Thankfully, the Canadian Election Study (CES) and Environics both tracked the evolution. Starting in 1987 Environics asked as part of its Focus Canada study, Canadian attitudes toward homosexuality. In 1987, 10% indicated that they approved of homosexuality (there were many unsures (30%) this year and in 1996). By 2004, this number reached 47%. Even setting aside the very low year of 1987, the increase from to 47% is remarkable. In a different approach, the Canadian Election Study asked respondents to rate homosexuals (Gays and Lesbians after 1993) on a scale from 0 to 100. The average rating for each survey rose from 45.5 to 73 out of 100 in 2011.The outsider nature of the community has broken down substantially in the last decade, particularly after 2004 (between 2004 and 2011 the average rating has increased much more than it did between 1993 and 2004).

Thankfully, the Canadian Election Study (CES) and Environics both tracked the evolution. Starting in 1987 Environics asked as part of its Focus Canada study, Canadian attitudes toward homosexuality. In 1987, 10% indicated that they approved of homosexuality (there were many unsures (30%) this year and in 1996). By 2004, this number reached 47%. Even setting aside the very low year of 1987, the increase from to 47% is remarkable. In a different approach, the Canadian Election Study asked respondents to rate homosexuals (Gays and Lesbians after 1993) on a scale from 0 to 100. The average rating for each survey rose from 45.5 to 73 out of 100 in 2011.The outsider nature of the community has broken down substantially in the last decade, particularly after 2004 (between 2004 and 2011 the average rating has increased much more than it did between 1993 and 2004).

Although history seems like inevitable march toward granting and accepting same-sex marriage, in 1999 a federal vote maintained the traditional definition of opposite sex relationships. While courts and Parliament were extending the same rights, the actual inclusion into the institution of marriage was being denied. Public opinion was divided and offered little in specific guidance.

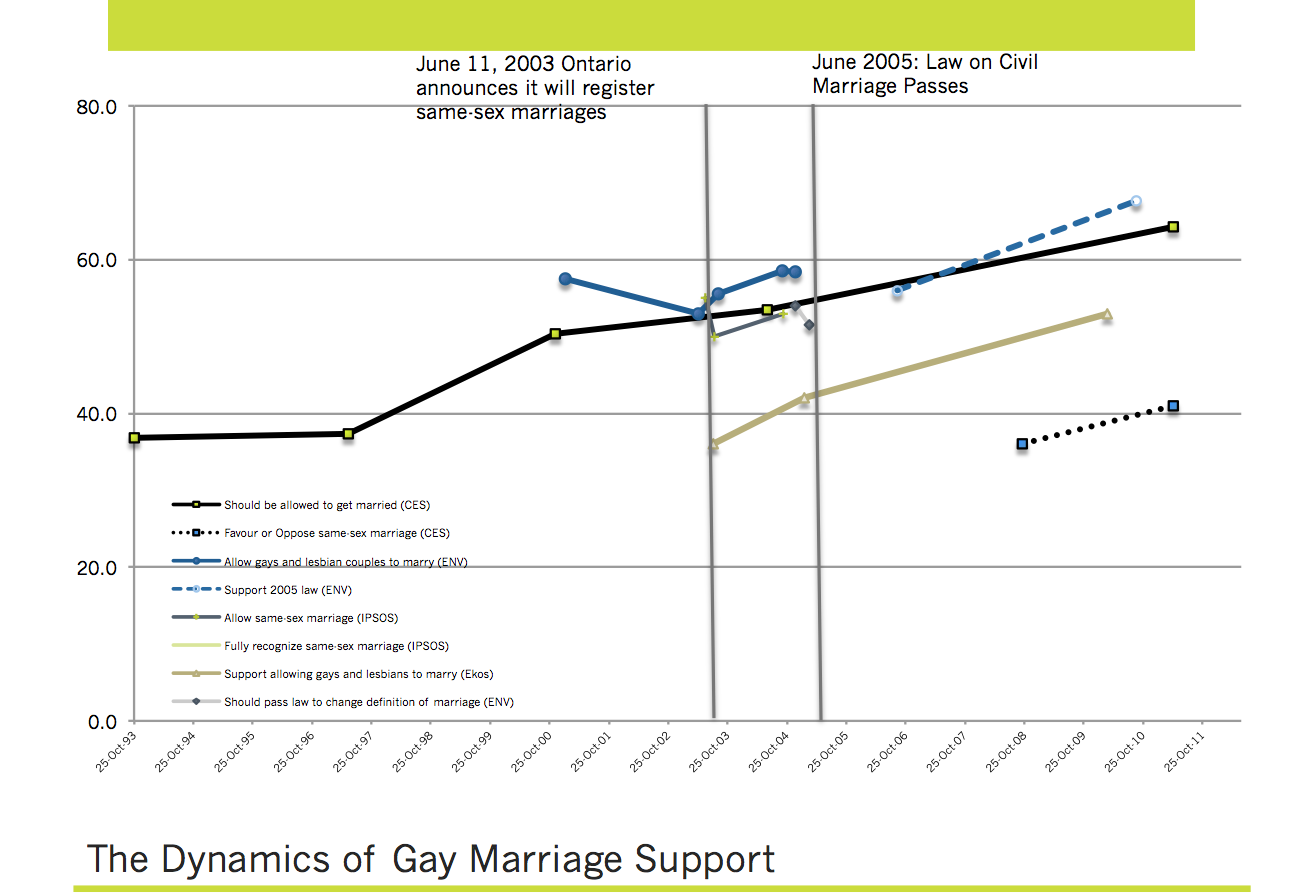

The chart below shows polling on the question over time from four polling firms. There were many other polls but often the questions were only asked once and this provides a very interesting as it is.

The CES surveys, which cover the longest period, show agreement that Gays and Lesbians should be allowed to marry rises significantly between the 1997 and 2000 elections. Note that in this period, the Supreme Court had ruled that same-sex couples have the same benefits and obligations as opposite-sex ones. The question of marriage was definitely on the agenda. Nevertheless, just 50% supported marriage at this time.

As the issue heated up, more polling was taking place and polls showed relatively little movement in attitudes. Most trend lines were not moving dramatically in either direction but overall most were showing support for same-sex marriage hovering around 50% depending on whether respondents were explicitly given an unsure or neither category (this is why the Ekos trend line is lower). All trend lines tend to be more positive once Parliament acted in a manner consistent with the court rulings.

One reading of the trend is that public opinion was divided but leaning toward accepting same-sex marriage but this misses a key element of public opinion at the time — the overall acceptance of same-sex relationships.

The questions in the figure above show the issue in terms of a binary choice — same-sex marriage or not. The reality is that There were fewer staunch opponents than it may seem. A TNS survey in 2004 found that 39% would support marriage and another 35% would support legal unions for same-sex couples.

Moving forward to recognize same-sex relationships in formal-legal way (possibly including marriage) was something that Canadians were overwhelmingly onside with. Courts said it had to be civil marriage and a healthy majority of Canadians now agree.

Canadian courts played a nontrivial role in bringing about same-sex marriage but they did so largely with public support. If courts were leading they found increasingly receptive audiences for their messages.

We are fortunate that the Canadian Opinion Research Archive is around to help preserve the cultural legacy of the public opinion research that has taken place in the past 3 plus decades. I draw on some of the data here along with searches of individual company websites.